Steve,

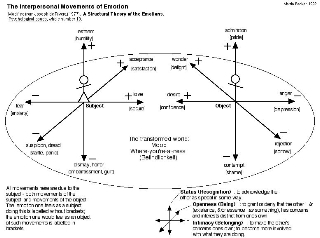

The diagram is just that, a synoptic look at a long monograph which

I recommend as a good read. Yes, de Rivera was offering a

"structural" - basically structuralist - analysis of the emotions.

The basic idea is that each emotion is a movement, often literal and

if not metaphorical, between two people. Each movement has both a

subject and an object: to put it in very simple terms, I can push

you away in anger, or I can withdraw from you in fear. In both cases

you are the object of the emotion, I am the subject. The movement is

in opposite directions, but in both cases it is along the dimension

of intimacy. Other emotions involve movements along two other

dimensions, which de Rivera names openness and status. The

experience one has as the object of an emotion is different from

ones experience as a subject. I should add that he has conducted

cross-cultural comparisons of emotion.

de Rivera does write about the situatedness of these movements,

though of course even the object of an emotion is in the world for

the person who is a subject. In fact, he argues that each emotion

provides a unique way of understanding a situation. For more of this

I always recommend the article by Hall & Cobey, 'Emotion as the

transformation of world.' So, on this analysis, although an emotion

is an interpersonal movement, and so social, it is *also* an

experience of the situation, and so individual.

I wanted to study moral conflicts, not in the form of what people

say when they are asked to reason about hypothetical moral dilemmas

(a la Kohlberg), but in terms of what people actually do. One clear

component of a real, first-person moral conflict is its

emotionality. How to look at that without reducing it to an

individual subjective experience, chaotic and irrational (the

empiricist approach) - or the result of some intellectual process of

appraisal (the rationalist approach, common among cognitive

psychologists)? What I came to argue was that emotion plays a

central role in conflict: it structures the situation in a way that

is immediate, unreflective, and with a strong sense of conviction.

It is a disclosure, a first way of understanding what has happened,

in action rather than in cognition, and it gives rise to practical

concerns (an impulse to confess, or seek revenge...). This has many

positive aspects, but it also makes it difficult to see the other

person's point of view, or even to recognize that they *have* a

point of view. The conflicts I studied only got resolved when people

talked, even if only to try to convince one another to do what they

considered the right thing, because then they found out that what

they had taken to be 'the facts' were only one interpretation. The

values behind the facts started to become evident. I think many of

us would recognize these characteristics of everyday conflicts.

Martin

On Jul 6, 2010, at 2:33 PM, Steve Gabosch wrote:

Martin, on the interesting chart you modified from de Rivera (1977)

with the 12 pairs of subject/object interpersonal movement of

emotions. It seems to deal with emotions in a decontextualized way

- we don't see the situations that create these responses. Am I

correct in that observation? The pairings it depicts are thought-

provoking, but I don't understand some or most of them. The whole

subject-object structure confuses me. The premise of the chart

that emotions are a way of being engaged in the world, and that

emotions are rational, or have rationality, makes sense - I am ok

with that - but I don't see how this chart is connected to the

world - it seems to detach emotions from their context. I just see

an interesting list of oppositions and groupings of emotions

without explanation. So I seem to be missing something. Could you

explain this chart a little?

On the topic in this thread, I agree with David K that abstraction

and generalization are two different processes. I am not convinced

yet that Vygotsky was always clear on that distinction - he seems

to conflate the two in Ch 5 in some places, for example, but seems

to have found great relief when he solved new aspects of this

question in Ch 6, criticizing the block experiments and their

thinking at the time for some important limitations in this

regard. At the same time, David points out the great pressures

bearing down on psychologists and pedologists in the early 1930's,

greatly distorting that conversation. Lots of puzzles to work out

in that Ch 5 to Ch 6 transition on concept formation theory.

- Steve

On Jul 5, 2010, at 3:30 PM, Martin Packer wrote:

On Jul 5, 2010, at 4:58 PM, Martin Packer wrote:

an emotion is an interpersonal movement.

systematic structure to the emotions, captured in the diagrams

with dimensions of intimacy, status, and openness.

there is a rationality to emotion - emotion is a way of being

engaged and involved in the world.

<Interpersonal movements of

emot.pict>_______________________________________________

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

_______________________________________________

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

_______________________________________________

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca