[Date Prev][Date Next][Thread Prev][Thread Next][Date Index][Thread Index]

RE: [xmca] Culture & Rationality

Peter,

I agree with almost everything you post here except the dichotomy verbal and nonverbal. I don't mean to by picky, but I think these term verbal thinking does not encompass the full capacity of human memory, thinking and reasoning that can be verbal but may also occur using "nonverbal" symbols and gestures. It is not just the "words", oral or written that give "speech" its meaning and significance. It is not the lack of human speech that makes babies comparable to the baser creatures, it is their capacity to develop language that makes them more than animals, and it is this capability of babies to enter into a dialogical and dialectical relationship that allows them to learn words and other symbols that are meaningful in their culture.

In Vygotsky, I think I started to understand this not from his use of language words directly ("speech", "language", "word" because that can get murky from English translations, was probably murky to begin with then and is still murky now), but through the discussion of language as a tool and extending discussions of semiotic mediation.

From: xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu [mailto:xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu] On Behalf Of Peter Feigenbaum

Sent: Thursday, June 28, 2012 9:45 AM

To: ablunden@mira.net; eXtended Mind, Culture, Activity

Subject: Re: [xmca] Culture & Rationality

Martin, Andy, (and Jennifer, from a crossing email),

I think Andy is pointing us directly to the heart of the matter, which I see as the divide between thinking nonverbally

(such as animals do) and thinking verbally. Verbal thinking is dialogical and dialectical. Nonverbal thinking

lacks these qualities.

Vygotsky's theory about the development of thinking and speaking forces us to wrestle with the question

of what causes a young child to transform from a nonverbal creature into a verbal one. We are not born

thinking dialogically; this is a form of activity each of us must learn in order to become competent speakers

of our native language. In practice, competent adults help young children participate in conversations by

performing much of the dialogical work themselves, thereby creating the illusion that young children are able

to *speak* dialogically on their own. But eventually young children must learn how to *think* dialogically in

order to truly master the activity of speaking. That's where private speech comes in.

In ontogeny, the development of learning to think dialogically is observable in children's use of private speech

in relation to their practical activity. Early in the process, private speech trails behind activity, giving voice to

children's thoughts but not appreciably altering the course of activity. Vygotsky referred to this relationship by

using an analogy to music: activity is the melody and private speech is the harmony. But gradually, the

relationship reverses: private speech becomes the melody and practical activity becomes the harmony.

This moment of transition is recognizable to us as the moment that private speech begins to show signs of

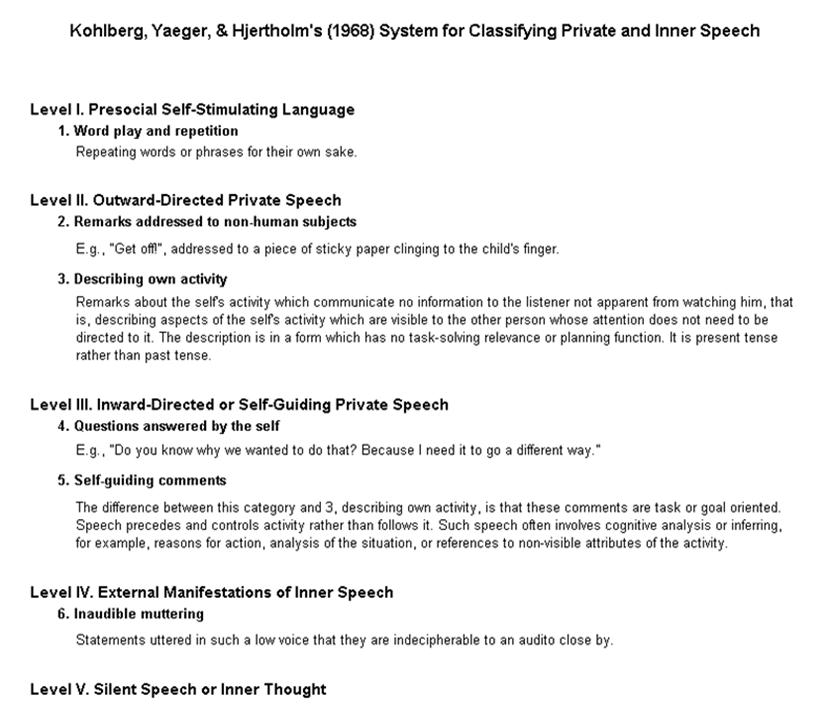

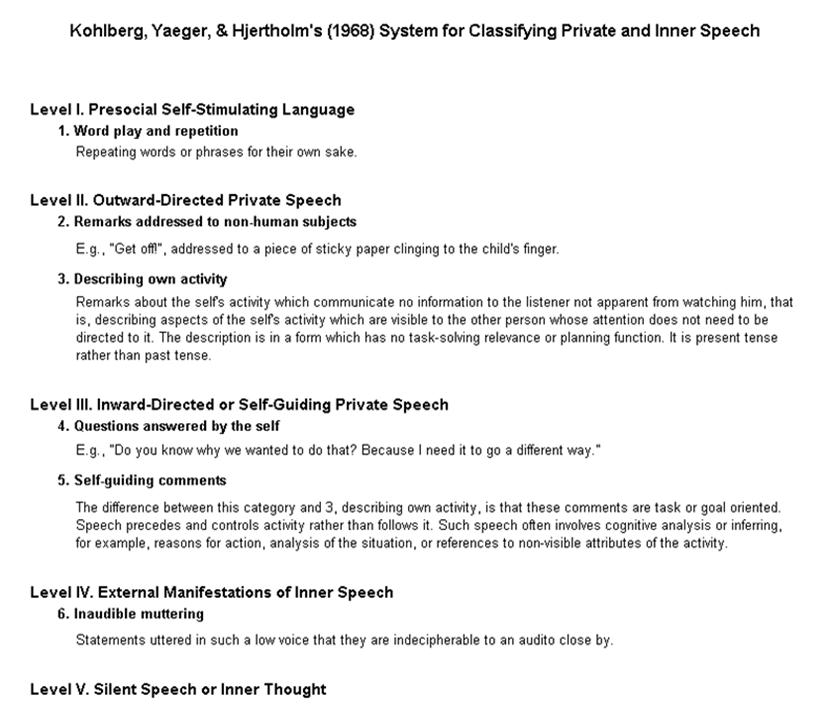

being *self-regulatory*, and thinking shows signs of being *self-reflective*. In Kohlberg's system for classifying

private speech (I know this came up in another related thread--see table below), this transition is marked by

the appearance of *Questions answered by the self*. Is there any better illustration that a person has mastered

the logic of dialogue than their being able to take both sides in a conversational exchange?

The relevance of this seeming digression has to do with Vygotsky's use of *scientific* concepts as evidence

that children have developed dialectical, rational thinking. In so doing, he also links rational thinking to

*schooling*, leading us to jump to the conclusion that *true* concepts are the product of education. While I

cannot cite any evidence (yet), I see no reason to believe that typically developing children have ever required

overt instruction in learning to think *dialogically*. Dialogical thinking develops in private speech as a result

of a child's own activity, not through explicit training or instruction--unlike scientific concepts.

If the developmental process of learning to master the activity of speaking and thinking occurs without instruction,

then primitive peoples should be able to think dialogically, although they may be unable to think *scientifically*.

This distinction might well be crucial to understanding the reasoning abilities of uneducated people.

Peter

[cid:image003.jpg@01CD5545.BCA2C260]

Peter Feigenbaum, Ph.D.

Associate Director of Institutional Research

Fordham University

Thebaud Hall-202

Bronx, NY 10458

Phone: (718) 817-2243

Fax: (718) 817-3203

e-mail: pfeigenbaum@fordham.edu<mailto:pfeigenbaum@fordham.edu>

From: Andy Blunden <ablunden@mira.net<mailto:ablunden@mira.net>>

To: "eXtended Mind, Culture, Activity" <xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>>

Date: 06/27/2012 09:09 PM

Subject: Re: [xmca] Culture & Rationality

Sent by: xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu>

________________________________

OK, I see what you are getting at, Martin.

I think one issue may be a certain conception of "rationality" or

thecapacity to reason. LSV makes it clear I believe that formal logic is

a barren conception of reasoning. Not just that it is an inferior

practice of reasoning than dialectical rationality, but a professional

misconception of what reasoning actually is.

In chapter 6 of T&S he reports research into what he claims is "true

concepts" which hinge around complelting causative and adversative

sentences: "Volya fell off his bicycle because ..." - will the child

add "... he went to hospital" or "he was careless." This may seem

strange. Doesn't this simply tell us about the child's concept of

causality? WHat has it to do with concepts?

The analytical philosopher at the University of Pittsburg , Robert

Brandom, who has never heard of Vygotsky (so far as I can tell) and

knows little about psychology, has made it his project to elucidate in

philosophical terms what a concept is. He says that a concept is two

things: (1) recognition of a situation, and (2) understanding of what is

meant by or what follows from that situation. He illustrates the idea

well by pointing to some "bad concepts" such as racist concepts which by

their nature identify a certain appearance with a contemptible character.

So the acquisition of concepts means precisely the formation

situation-significance pairs, and it is these pairs which function as

the substance of life and rationality in any culture and the substance

of mind for any individual member of a culture.

So I think it is a mistake to identify rationality with the habitual use

of formal logical reasoning. That formal logic constitutes a standard of

rationality (rather than the rules of a very narrow specialist domain of

reasoning) is an illusion of one particular current of philosophical

thought, one which the LSV who wrote Thinking and Speech did not share,

Uzbekhistan notwithstanding.

Andy

Martin Packer wrote:

> Hi Peter,

>

> I am glad to see you join in the discussion, since I know you've done interesting research on inner speech.

>

> I am certainly willing to grant that patterns of social interaction will become patterns of self-regulation and thereby parts of patterns of individual thinking. It also makes sense to me, and in my opinion LSV clearly states the view, that the higher psychological processes are cultural processes. I think he goes so far as to say that reasoning is cultural.

>

> But, importantly, that is not the same as saying that reasoning *varies* across cultures. We *all* live in culture, and one can say that reasoning is cultural and still maintain that reasoning is universal. Are we willing to take another step, and suggest that in specific cultures the ways that people reason will be different, because the specific conventions of each culture are involved? That is a big step to take, because the rules of logic, to pick what is usually taken to be one component of reasoning, are usually considered to hold regardless of local conventions.

>

> One way to take this step, of course, is to say that people in cultures reason in different ways but then to add an evaluative dimension. Those people in that culture reason differently from the way we do, but that is because their reasoning is less adequate than ours. They are more childlike, more primitive. *This* move has often been made, and I can find many passages in LSV's texts where he seems to be saying basically this. That's not a move I find interesting or appealing, and it's not what I am proposing.

>

> On the contrary, it seems to me that much of LSV's writing can be read as pointing to the conclusion that *standards* of rationality will vary from one culture another. But I don't think he followed his own pointers, and, as I've said above, it is a pretty radical conclusion to come to.

>

> Martin

>

> On Jun 27, 2012, at 9:33 AM, Peter Feigenbaum wrote:

>

>

>> Martin--

>>

>> If you grant that interpersonal speech communication is essentially a cultural invention, and that private and inner speech--as derivatives of interpersonal speech communication--are also cultural inventions, then Vygotsky's assertions about inner speech as a tool that adults use voluntarily to conduct and direct such crucial psychological activities as analyzing, reflecting, conceptualizing, regulating, monitoring, simulating, rehearsing (actually, some of these activities were not specifically asserted by Vygotsky, but instead have been discovered in experiments with private speech) would imply that these "higher mental processes" are themselves cultural products. Even if the *contents* of inner speech thinking happen to bear no discernible cultural imprint, the process of production nonetheless does.

>>

>> Of course, you may not agree that interpersonal speech communication is a cultural invention. But if you do go along with the idea that every speech community follows (albeit implicitly) their own particular conventions or customs for: assigning specific speech sounds to specific meanings (i.e., inventing words); organizing words into sequences (i.e., inventing grammar--Chomsky's claims not withstanding); and sequencing utterances in conversation according to rules of appropriateness (i.e., inventing rules that regulate "what kinds of things to say, in what message forms, to what kinds of people, in what kinds of situations", according to the cross-cultural work of E. O. Frake), then reasoning based on the use of speech must be cultural as well.

>>

>> My guess is that you are looking for evidence that cultures reason differently. While there may be evidence for such a claim, I only want to point out that the tools for reasoning are themselves manufactured by human culture.

>>

>> Peter

>>

>> Peter Feigenbaum, Ph.D.

>> Associate Director of Institutional Research

>> Fordham University

>> Thebaud Hall-202

>> Bronx, NY 10458

>>

>> Phone: (718) 817-2243

>> Fax: (718) 817-3203

>> e-mail: pfeigenbaum@fordham.edu<mailto:pfeigenbaum@fordham.edu>

>>

>>

>>

>> From: Martin Packer <packer@duq.edu<mailto:packer@duq.edu>>

>> To: "eXtended Mind, Culture, Activity" <xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>>

>> Date: 06/26/2012 05:06 PM

>> Subject: [xmca] Culture & Rationality

>> Sent by: xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu>

>>

>>

>>

>> Thank you for the suggestions that people have made about evidence that supports the claim that culture is constitutive of psychological functions. Keep sending them in, please! Now I want to introduce a new, but related, thread. A few days ago I gave Peter a hard time because he wrote that "higher mental processes are those specific to a culture, and thus those that embody cultural concepts so that they guide activity."

>>

>> I responded that I don't think that LSV ever wrote this - his view seems to me to have been that it is scientific concepts that make possible the higher psychological functions (through at time he seems to suggest the opposite).

>>

>> My questions now are these:

>>

>> 1. Am I wrong? Did LSV suggest that higher mental processes are specific to a culture and based on cultural concepts?

>>

>> 2. If LSV didn't suggest this, who has? Not counting Peter! :)

>>

>> 3. Do we have empirical evidence to support such a suggestion? It seems to me to boil down, or add up, to the claim that human rationality, human reasoning, varies culturally. (Except who knows what rationality is? - it turns out that the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy does not have an entry for Rationality; apparently they are still making up their minds.)

>>

>> that's all, folks

>>

>> Martin

>>

>> __________________________________________

>> _____

>> xmca mailing list

>> xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>

>> http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

>>

>> __________________________________________

>> _____

>> xmca mailing list

>> xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>

>> http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

>>

>

> __________________________________________

> _____

> xmca mailing list

> xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>

> http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

>

>

--

------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Andy Blunden*

Joint Editor MCA: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/hmca20/18/1

Home Page: http://home.mira.net/~andy/

Book: http://www.brill.nl/concepts

__________________________________________

_____

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu<mailto:xmca@weber.ucsd.edu>

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca

__________________________________________

_____

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca