Date: Wed Sep 24 2008 - 07:01:43 PDT

If this email was posted successfully the first time around, please accept

my apologies for this one in response to gremlins unnamed.

_____

From: Paula Towsey [mailto:paulat@johnwtowsey.co.za]

Sent: 24 September 2008 02:52 PM

To: 'xmca-bounces@weber.ucsd.edu'; 'David Kellogg'

Subject: RE: [xmca] The Strange Situation and picking up the threads

Dear David and the Study Group

It's a holiday here today which gives me time to pick up on some of the

threads you wrote about, David. And seeing it's a holiday, my weaving here

is more conversational and less chapter and verse - but in the process,

hopefully, without too many glossings-over or glitches - and I hope this is

okay with you.

I have on occasion found it helpful to view Chapter 5 of Thought and

Language as an executive summary to the extensive and more detailed research

work which underpins it. This research work, as I see it, would include

that of Vygotsky, Sakharov and company on the more than three hundred

subjects referred to in the chapter, and also could include the work done by

other scholars in the intervening years. Viewing the chapter as an

executive summary allowed me to forgive it for being frustratingly vague at

some times and to make allowances for the lack of presentation of empirical

examples when it is rather assertive at others. I think this also helps me

with its implicitness as coming before Chapter 6 and after Chapter 4,

coupled with its almost wholesale importation by Vygotsky four or five years

after the work had been conducted: the implicitness, for me, is that it has

links to the other chapters but one needs to find them. And tracing

threads, David, is a good way to do this, I think.

Some of the threads I've traced are in connection with what to me are the

most obvious differences in circumstance between a child learning a

rationalist concept al la Chapter 6 compared to al la Chapter 5, because,

for me, these threads link back to what's missing in Chapter 5: for

starters, the ZPD; the enrichment by everyday concepts; and no contextual

cues.

So, then, first to the contextual cues (the directing influence of adult

speech): the blocks are a method of double stimulation in that there are

objects of the activity (the blocks) and signs which help to organise the

activity (cev, bik, mur, and lag), as well as an experimenter, but there is

no contextual clue for the children to pick up on. There's no adult

involvement in usage as there is in 'house' and 'brother', and, equally,

there's no presentation of the funny words as a system of interrelated ideas

as there would be in explicit instruction for 'revolution' and

'hibernation'. This is for me the 'freedom' that Vygotsky writes about

which allows experimenters to see how children go about forming new concepts

without interference from the context of word usage that points to their

meaning: sure, the words do have a meaning that the experimenter has in mind

- and children under 14 in my study were given the idea the words came

(possibly) from children near the North Pole and so therefore they have some

kind of meaning - but the lack of contextual clue makes the

learning/problem-solving activity of the blocks more like presenting

children with a list from a dictionary - the meaning is there but you have

to ascend to the concrete to get to it.

And then, next, there's the absence of a ZPD - at least overtly - and at

least one which wasn't discussed or bandied about when the work in Chapter 5

was being done. Yet, in the blocks situation, when children are able

overcome the bewildering confusion of colour and shape, and when they are

able to be guided by the notion that the words mean something in particular

and are not just another characteristic of the blocks (ie, as more than

merely denoting that different names indicate a different kind of block and

as more than simply another characteristic like colour or shape), these two

abilities point to whether the task is within or above their zone of

proximal ability. In the DVD which I posted to you and Eric yesterday, you

will see something about intervention that I won't discuss here until you've

seen the DVD, but what I can tell you is that I intervened with six or seven

of the five-year-olds as I do in the DVD and the results were very

different. But the thing for me about the blocks is that they are not about

the ZPD: if anything, they're there to counter the supposition that some

scholars may have in believing that anything can be learned by a less

capable peer, irrespective of their level of intellectual development; the

types of connections they are likely to make; how consistent they are likely

to be in focusing on these connections; and whether they are able to take

advantage of the means provided for them in the learning situation or not.

The bottom line of these blocks, for me, is that they show the types of

connections that children would be most likely to make in the absence of a

contextual clue.

And, thirdly, enrichment by everyday concepts: just as a thought experiment,

David and the Study Group, how would your notion of everyday concepts be

affected if you were to consider that part of their richness and complexity

is due to the inconsistent, wobbly, 'because-they're-different',

flexible-to-the-point-of-not-bothered-by-contradictions,

'what-do-you-mean-I-have-to-grasp-the-task-as-a-whole-to-see-the-bigger-pict

ure-and-the-overall-system?', the solipsism of syncretic perspectives, and

all and any of the other (wonderful) characteristics that can be found in

Vygotsky's discussion of preconceptual reasoning? When I do this, my

appreciation for the processes involved in constructing 'everyday' concepts

- and in the way we play with and invent new words - is immeasurably

enriched, and I become a bit of a complex detective.

And then, if we extend this thought experiment further, to the traces of

complexes which may exist in many kinds of language usage by adults (eg,

Kozulin's great discussion on the kinds of 'gates' since 'Watergate'), then

perhaps we can appreciate how widespread these kinds of complex reasoning

strategies are. BUT (to use David's form of emphasis), the important thing

as I see it about finding complex-type thinking strategies and approaches

lurking in one form or another in the world around us is this: what

distinguishes a child's complex thinking from an adult's is that the child's

is INCONSISTENT. You and I have a system to compare things with, to

juxtapose (or, as Patrick Miller says, "to juxtasuppose") things against; we

have the ability to do this far more consistently than the children in the

blocks situations do, or, at the least, we have, or can have, an awareness

that we're being inconsistent. But the children who're inconsistent in

their approach to the blocks (or in working out the essential as opposed to

the functional characteristics of a group of blocks or a new word) aren't

doing this because they're being ornery, but because they can't be

consistent, because they're learning how to generalise and to abstract, and,

it seems to me, part and parcel of this learning is becoming more consistent

and aware of your actions (the conscious realisation and mastery, David?).

The reason I make this kind of statement is because in my experience with

the blocks an adult would never say "I put this one here because it is the

same shape, and this one here because it is the same height, and this one

here coz it's the same shape as that one next to it and the same colour as

the one next to that."

David and the Study Group, there are so many layers and levels to working

with the blocks and I hope to get the opportunity to discuss the ones I have

come across with you. At ISCAR I was able to compare notes with Mohammed

Elhammoumi (who's worked with them since 2001) and find that children in

Southern Africa and Saudi Arabia were doing the same things with the blocks

(although, to be sure, with cultural variation: for example, towers were

described as the House of the Big Bad Wolf in one part of the world and as a

minaret of a mosque in another(!)).

So now to pick up on some of your threads email. David, you wrote:

I think the gap between Chapters Five and Six is just one of the most

obvious of these pieces of the tapestry that needs patching. I also think

that LSV himself knew this, and he lets us know it:

"The system which emerges with the scientific concept is fundamental to the

entire history of the development of the child's real concpts. It is a

chapter of that history that is inaccessbile to research based on the

analysis of artificially or experimentally formed concepts." (Minick Trans.

pp. 223-224)

And my response is that I agree absolutely with Vygotsky's assertion here

(and with the substance of your argument, David), because to my mind the

italics should be around the words "The system". Because, firstly, I

believe that a 'system' depends on an ability to abstract and to generalise

consistently, and that, secondly, the blocks experiment as conducted by

Vygotsky and Sakharov, which seems is a more cumbersome approach than the

slightly different variation suggested by Hanfmann & Kasanin (and which I

found makes the whole process more flowing and less contrived), did not,

according to Vygotsky, allow for hierarchical thinking or generalisation

building mechanisms to be revealed. But these don't just, I believe,

pertain to the 'absence of a system' or, because it is another 'chapter',

negate the generalisability of the blocks findings. In the case of the

presence or absence of a system, Valsiner's analysis and Van der Veer's

argument elsewhere bring to light the meaning-making elements of the method

of double stimulation, inherent in the processes and actions of the

participants, and on the individual/individualised sets of experiences that

the subject brings to the experimental situation (and over which the

experimenter has little control) and which will influence how the subject

takes up or responds to the experiment. And then, as far as the

inaccessible chapter is concerned, for me the point that Vygotsky is making

here is that "THE SYSTEM" is not revealed in the study of artificial

concepts, perhaps because the blocks were never designed to provide an

account of systematic, 'scientific', rationalist thinking - what they were

designed to do was to allow the development of concepts spontaneously to

unfold before the experimenter, to demonstrate what happens when there is

'the absence of a system', and where there is no contextual clue. I've

included just one example below of how I've discussed aspects of this

before:

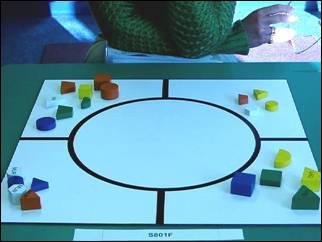

In the photograph below, this subject (S801F), twelve minutes into

the session, demonstrated several aspects of Vygotsky's assertions: what the

method of double stimulation allows to be seen in concept and language

development when "freed from the directing influence of the linguistic

milieu" (1986, p. 120) and "the absence of a system" (p. 205) in spontaneous

concept development.

In this subject's (S801F) explanations for the four groups, there continued

to be a lack of a consistent principle across them.

The mur blocks (bottom left) were now described as "tall, not as short;

round", whereas previously, they had been "pointy". When the subject's

attention was drawn to the mur triangle, she said "and one's not round".

The cev group (top right) was described as "short".

The bik group (top left) was described as "feelings", where the lag circle

had been placed next to the lag square of the same colour; the trapezoid was

put next to the triangle (flat?), and the green semi-circle next to the

green trapezoid (colour).

The lag group (bottom right) had been described as "the square ones" and

when the subject's attention was drawn to the blue bik circle, she had just

moved it across to the bik group before this photograph was taken (and the

yellow bik semi-circle remained in the group of "square ones").

And then, in relation to more than the presence or absence of a system, what

I agree is lacking here - and which I need to read more about (perhaps you

can provide me with pointers) - is where in Vygotskian psychology is an

account provided for the arrival of scientific, rationalist, abstract,

systematic thought? What is the explanatory mechanism which accounts for

it? If it is the social, then where did the socials get it - from the

history of previous generations of (adult) socials? From each other?

Piaget, I seem to remember, argued for reversibility.

Another thread, David, is where you wrote:

Shortly after this passage, he explicitly discusses why he thinks that

syncretic concepts, complexes, preconcepts and true concepts do NOT

correspond to the logical structure of concepts as learnt by the child in

school.

This is quite consistent with what he said in Chapter Five (on p. 161 of

Minick and elsewhere) about the difference between the concept as defined

and the concept as developed under experimental conditions: the

psychological categories revealed by Sakharov are based on the concept of

inclusiveness rather than logical hierarchy (that is why LSV harps so much

on the "rose" "flower" "plant" example).

To answer you in two parts: Firstly, I think, as I mentioned to you in a

previous email, that what you didn't provide in your fantastically mammoth,

rather-than-watch-Harry-Potter analysis of Chapter 5 was the potential

concept. By including the potential concept alongside the complexes, we get

two sides of the equation: generalising is what complexive thinking is

learning to do, and abstracting is what potential concepts are learning to

do. I would also argue that one needs a system that is more than merely

comparing 'same' and 'different' in order to be inclusive. Secondly, as I

have argued elsewhere, while it is true that the blocks don't allow

themselves to be thought of in hierarchical terms, it is only when one has

abstracted and generalised across two not readily noticeable characteristics

of the blocks (height and size), when one is able to do this without losing

sight of them once abstracted, and when one is able to assign them

hierarchical prominence (as opposed to concrete and factual observations of

what the blocks look like), it is then that one is able to conceptually

solve the problem of the blocks by framing the solution in terms of the

double dichotomy.

And then, David, concerning what you wrote about freedom and attention spans

and why I will continue to argue and present you with evidence to

demonstrate that the results of these blocks experiments, whether they be

Vygotsky's, Sakharov's, Stones & Heslop's, Mohammed Elhammoumi's or mine,

are not merely the results of 'strange situations':

At the very least, I think we need to accept what LSV says on p. 143 of

Minick's translation: "the child is not in fact free to develop the meanings

he receives from adult speech", and so the Sakharov experiment does merely

show us something hypothetical; what the child would do about concepts IF

the child were free to discover for himself the meanings of adult speech

(and also IF the child had an almost unlimited attention span!)

And that brings me to your first comment, about the extent to which the

Sakharov experiment can be said to be eco-specific. Rene van der Veer and

Valsiner (in Understanding Vygotsky) points out that the experiments were

VERY time consuming. This alone makes it strange situation, I'm afraid.

We can add an adult to make sure the child stays on task, of course. But it

will be a strange adult and it will make the situation even stranger.

Nor does it make the time significantly longer. The materials used in

Chapter Six cover a span of two years (and even then LSV feels obliged to

"extend" it hypothetically into a parallelogram of development which covers

the whole of elementary school. How can we compare an experiment, no matter

how long, to six years of school experience?

In response to your first paragraph here, my discussion of 'what's missing

in Chapter 5' at the start of this email offers my perspective on your

argument here.

And next, in response to the accusation of a very time consuming process

(and therefore a strange (and-to-be-discounted?) situation), I agree that

the approach discussed by Sakharov appears very time-consuming and stilted.

Now because it was my intention to conduct a replication of the original

study and its results, I admitted upfront in my paper that I was unable to

find evidence that links the original blocks and their specific method with

the particular method of double stimulation that we in the West have

inherited from Hanfmann & Kasanin. To put it simply (despite the danger of

oversimplifying things), I began my approach for each and every subject with

what I could glean from the Sakharov approach (focusing on one group at a

time) or the Hanfmann & Kasanin approach (which combines the options of

putting 'the blocks you think are the same as this kind, mur, here' with

trying to work out what the four groups could be right from the beginning),

depending on the cues that I got from each of the subjects, irrespective of

their ages. Then too, there is the aspect that Mike touched on, concerning

the behaviour of the experimenter, both inside and outside of the blocks

procedure. So much depends on the personality and behaviour of the

experimenter that is more than only the sensitivities paid to the subject:

as far as these sensitivities are concerned, though, I am a teacher (both

ends of the spectrum - preschoolers and adults) and so my sensitivities to

attention spans and emotions and getting it right or wrong and boys and

girls and games for kids and solutions that escape me even though I'm an

intelligent adult - all of these are the kinds of 'stuff' that we dealt with

and which in some measure is reported on in the scoring approach of Hanfmann

& Kasanin - both qualitative and quantitative, with their caveat about the

quantitative being considered incoherent without the corresponding context

of the qualitative.

And so how can we compare a long and strange situation with six years of

schooling? I hope my threads here will go some way to persuading you and

the Study Group that it is possible and also that following threads from the

journeys each of us takes before arriving at where you write the following

(and where we kind-of agree) is really what the social construction of

knowledge is about:

I think that's why Vygotsky is willing to accept that Sakharov's experiment

reveals processes that do not go away but play an important role in REAL

concept development; he believes that the categories of syncretism,

complexive thinking and preconcepts are all there even in the child's school

based thinking because underlying each is a mental act of generalization

which is not based on perception and memory but rather on conscious

awareness and mastery.

And also where you write:

In some ways, I think that Chapter Seven contains some of the answers I'm

looking for:

a) the compatibility of complexive thinking and even syncretism with

conceptual thinking is not absolute, but it is real: we can see it in poetic

language, and also in metaphor, upon which scientific thinking is highly

dependent (Halliday 2006).

b) conceptual thinking is not particularly widespread in modern man.

Concepts are based on language, but things are not at all the other way

around: language is by no means a matter of creating counters for concepts.

I do hope that we don't have to wait for another public holiday before I

manage to talk to you again because there remain many of the questions you

asked as yet unanswered by me - but perhaps the lack of public holidays is

just as well, because shorter and sweeter answers would probably be more

appreciated by everyone!

Paula T

Ps - I don't know if they (Columbus and Franklin) were complexifying when

sailing and Northern Passaging: perhaps what they were doing, which could be

the nub of scientific thinking, was building on the incomplete rather than

the pseudoconcept, because they were seeking those elements that were

essential (and which guaranteed survival) as opposed to merely functional

(which would allow for more day-at-a-time solutions). I think.

_______________________________________________

xmca mailing list

xmca@weber.ucsd.edu

http://dss.ucsd.edu/mailman/listinfo/xmca