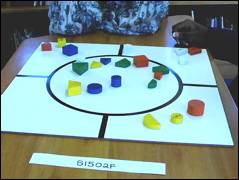

FIGURE 23 (S1502F): Pseudoconceptual reasoning in an elaborate diffuse complex

The fifteen-year-old

participant in Figure 22 (S1502F) seemed to rely on perceptual clues to a large

extent without hypothesising very much in advance (she was a rather timid

subject). However, she said she

was comfortable (when prompted about it) that her groupings were not consistent

across the four groups. Her

response indicated less concern with the implications for the totality, and,

although she did solve the problem of the blocks, she did so by apparently

being more perceptually guided rather than conceptually once other tentative avenues

to solve the problem had been tried.

Prior to Figure 23, this participant started by immediately assigning different shapes to the corners, creating groups of triangles, squares, circles, and trapezoids. She asked if she needed to place all of the blocks when she was faced with the two semi-circles and two hexagons left over in the middle. The semi-circles were then added to the circles, and after some discussion, the hexagons to the trapezoids: this resulted in two groups on shape and two with half-shapes and their counterparts within each of these two groups (elegant, but inconsistent across the four groups).

However,

when the next clue was revealed – the mur square

– this participant was rather unsure of its implications because it was a

different colour and shape from the triangular mur exemplar. She was at

that stage unable to advance any other ideas, and after some time asked if

there was a pattern created by the blocks in each group. She suggested an idea of cutting the

squares in half to make triangles (she’d suggested that the squares could then,

in this way, be possible mur blocks, although I suggested

that this would result in different types of triangles – equilateral rather

than isosceles). The participant

then suggested representative allocation of one shape per group (without

counting them first to see if this was possible), but gave up on this idea even

before one complete group had been created (for no given reason). Two more clues were provided and, after

hesitantly placing only two more blocks, the subject asked if she needed to add

more of the leftover blocks.

The photograph depicted in Figure 23 was taken 20 minutes into this session. We had earlier explored whether halving the squares could be a solution which would allow a group of squares and triangles in one group (isosceles rather than equilateral triangles notwithstanding). With the newly turned bik trapezoid (top right), the participant returned the two squares which had been placed alongside the bik triangle to the middle and explained that this move would allow the two hexagons to be included in this group. Her pseudoconceptual grasp of these implications could be seen in a number of ways: firstly, we had explored and eliminated the “cutting-in-half” theory in regard to hexagons and trapezoids as well as the square/triangle debate; secondly, the bik triangle and the bik trapezoid (with their names revealed) could not result in hexagons when put together; and, thirdly, she made no attempt to remove the lag square from the mur group at top left, or the semi-circle from the cev group at bottom right. However, she seemed to hold on to this idea of the cutting-in-half approach while she tentatively explored other possibilities. Her incomplete appreciation for the moves she was making in relation to the totality was also evident here in that there were only three groups, which remained as such until near the end of her session when she grouped the blocks according to size.