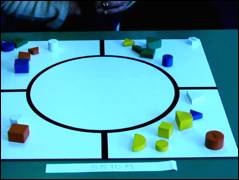

FIGURE 10 (S510M): Pseudoconceptual reasoning within a collection complex

The five-year-old participant in Figure 10 (S510M) began by creating a group of orange and a group of white blocks, and then extended this to two more groups starting with yellow and green each. His explanation and his running commentary as he went along was that in each of the groups there were some colours of the same kind in the middle, with colours of a different kind at either edge. To begin with, each group did start with a central grouping of colours, which was followed by what could be interpreted as random placing after this. However, the participant did not rapidly place these blocks: he placed them with deliberate care, often moving a block from one group and deciding to place it in another. Even so, this collection method of sorting the blocks was conducted with scant regard for the implications of these moves in relation to the overall task.

Pseudoconceptual reasoning, as reflected in this inability to conceptualise the task as a whole, was further evident in the participant’s reaction to contradiction: this reaction was a flexible shift of emphasis from one element to another without being concerned about the implication these shifts had for consistency or coherence.

The first moment of correction for this participant followed his initial collection-type approach when a newly turned block resulted in his reasoning that the names of the blocks referred to the colours of the blocks. He made this comment after (fortuitously) one sample of each of the different groups had been turned over. However, as two orange blocks (a lag circle and mur triangle) were in this turned-over group, it was suggested to him that if the names were for the colours, that two colours had not been “named” yet. He selected a blue bik circle, turned it over and placed it next to the green bik trapezoid. After observing this arrangement (top left, slightly obscure) for a moment or two, his reaction to this contradiction was to fluidly shift his emphasis to the area where the blocks had been placed.

Yet another contraction resulted in his deciding that the names of the blocks, when revealed, simply meant that the blocks had to be put together with the other blocks which had the same name and that this denotative function was all there was to it: it did not appear to mean anything about the characteristics of the blocks in that particular group except that they had the same name (possibly, as Vygotsky observed of complexes generally, as a classic example of things being connected as a family with the same name – where the name (irrespective of other differences) means that things belong together (where Granny Smith may look and behave very differently to Jimmy Smith who is a toddler, and to James Smith, his daddy, but where they are all Smiths)).

This participant’s own rules for his game with the blocks emerged increasingly as his session progressed, so I allowed him to turn the blocks and to group them as he saw fit. As his running commentary continued, with the system of forfeits being introduced, his own rules took over to the extent that this researcher became an outsider to a game of bewildering complexity.