Four episodes of joint paper reading: Lotman, Wells, Bateson and

EngeströmI would finally like to return to the problem of harnessing

the multilogical spontaneity of a scholarly mailinglist. The Xlists have

certainly provided a conducive space for the learning of individual

participants, and contributed to the renewal of the community of

practicioners of CHAT approaches. The forum has also served as a channel

for crossfertilization of diverse discourses, brought to the virtual

setting by participants from different disciplinary fields. Arguably the

Xlist discussions have also been enriched by research collaborations

between list participants - here I am thinking particularly of the

international project on Acting in Culture, proposed in 1992. However, a

scholarly mailinglist is more suitable as a setting for learning than as

an setting for actual collaborative research, the list community being too

loosely structured to serve as a channel for collaborative production of a

definite result (Lewenstein, 1995). As far as I know the few attempts at

collective writing over the Xlists have foundered. This is the flip side

of mailinglist self-regulation in the several senses of the term:

socially, technically and as an emergent process.

Concerns for cumulativity and development on the collective level have

prompted core participants to explore ways of harnessing the multilogue by

inserting planned activities into the Xlist setting: exchanges between

local seminar groups, Xlist channeling of communication between similar

courses run at separate locations, setting up of special-purpose

subconferences, joint readings of papers or entire books etc. Here I have

chosen to briefly examine four episodes of joint reading of paper-size

publications, all highly relevant to recurring concerns in the repertory

of Xlist multilogues.

- A reading of Lotman (1988) in the autumn of 1990

- A reading of two pre-publication papers by Wells (Wells, 1993 and

Wells & Chang, 1997) from a methodological perspective in the autumn

of 1992

- A reading of Bateson (1972) in the winter quarter of 1993

- A reading of Engeström (1996) in the autumn of 1996

The

paper selected for a joint reading in the autumn of 1990, Yuri Lotman's,

"Text within Text" (Lotman, 1988) deals with theorizing the relation of

stability and change, closure and open-endedness in language and in

text.The paper is theoretically relevant to many recurring Xlist issues

about intersubjectivity, communication, and relations between text and

context. Lotman argues that text has the dual functions in a cultural

system of on the one hand conveying meanings adequately and on the other

hand creating new meanings. There is an irreducible tension between the

univocal, transmissive function of text and its dialogical function as a

"thinking device". The paper is aptly brought in as a target for joint

reading in the context of a discussion of communication and

miscommunication - a multilogue taking place in the second week of

September 1990. However, the coordination of the event turns out to take

much more time and effort than was anticipated in the initial suggestion.

The journal is not easy to get hold of, and a distribution of photocopies

has to be arranged, so that instead of beginning within a week, it takes

five weeks before a summary of the first part of the article is posted as

a signal for the event to begin. By then the collective enthusiasm has

moved on to other objects - issues about literacy, cross-cultural

research, microgenetic studies, and, eventually, the ethics of videotaping

as a method of collecting data. A few participants contribute to keeping

Lotman in the mailflow, but the exchange is very sparse: there are all in

all 13 Lotmanian discussion postings spread out over 36 days and with

relatively few links between them. On the other hand, the event is one of

the rare episodes that does have a beginning and an end - the paper is

summarized in three sections, and there is a final posting providing

uptake and rounding off after the last summary. There is also evidence in

the archives that the event made a mark in the community: there is at

least one of the longterm Xlist participants who comes back to this paper

more than once, and after months and years - after having been among those

who initially asked for the paper in public because of access problems.

The Lotman episode provides an example of how the spontaneous flow of

multilogue does not sustain the collective patience to hold a topic in

suspension for weeks, for collective action to be taken to provide it with

coordinated grounding in the virtually simultaneous reading of external

material.

The two pre-publication papers by Wells (Wells, 1993 and Wells &

Chang, 1997) chosen for a joint reading in the autumn of 1992 both deal

with the co-construction of meaning through discourse in the classroom,

and the implications of classroom discourse for learning and development.

These are educationally central questions that Xlist multilogues return to

over and over again. However, in the case of this particular event of

joint reading, the papers were not chosen as a target with the purpose of

discussing the educational implications of their results, but for the

purpose of providing a common ground for a suggested discussion of

methodological issues of Activity Theory and data gathering methods like

classroom observation. Issues of methodology and of ideological influence

on research have been around in the Xlist mailstream throughout October

1992, when one contributor posts a request for literature on the topic of

research methodology, and also suggests a number of questions for

discussion on the mailinglist. There are a number of postings giving

bibliographic references over the next few days, and there are also a few

that take up the issue of methodology in response to the questions. Then

it is suggested that it would be a good idea to ground the discussion in

particulars by using some research paper, preferably one with extended

excerpts from classroom discourse so that the process of analysis can be

made visible. The Wells papers are nominated (and agreement obtained from

the authors), and there is an exchange of postings about how the event

should be organized. It is decided that the discussion is to be channeled

into the XCLASS, and the papers to be distributed electronically for the

asking. The initial questioner volunteers to serve as facilitator of the

discussion. Like in the Lotman reading, this episode results in very

little discussion of the intended nature - after the putative start of the

reading event the first week in November there are 11 postings that

recognizably belong to this thread, 7 in the first week and another small

batch of 4 postings after a gap of two weeks, when one contributor asks

when the discussion is supposed to start. In this episode there are three

times as many messages of an administrative character: discussion of the

organization of the event, requests for the papers and for being

subscribed to the XCLASS subconference. Of course there is no knowing how

much of a multilogue on methodology there would have been without the

transformation of the event into a joint reading, but the delay caused by

having a paper distributed and perhaps the very process of organizing the

event over the mailinglist channel, may have diverted the collectively

available time. Limited time for reading the paper carefully enough to

have opinions on its methodology will also have had its effect.

The essay by Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference", included in

Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972), was chosen for a joint reading in the

winter quarter of 1993. Bateson argues for the theorizing of the simplest

unit of mind as an elementary cybernetic system with its messages in

circuit, where the transform of a difference traveling in the circuit is

the elementary unit of ideas. This paper contains two illustrative

examples of such systemic circuits - mind extending outside the boundary

of the skin - that have been recurring objects for Xlist discussion: the

blind man with his stick and the man cutting down a tree with an axe. It

is one of these Batesonian occasions that prompts the suggestion for a

joint reading: Bateson has been invoked several times in the Xlist

mailstream of December 1992, when a joint reading of this particular paper

is suggested. The suggestion is taken up by other participants, but the

matter of organization is quickly channeled outside the public forum,

directly to the contributor who initiated the topic, and who has

volunteered to facilitate the discussion. The second week of January 1993

this participant announces that the Bateson reading will start on February

first, with the first pages of the essay - but it is not until a few days

later that he starts the discussion by forwarding a commentary on the

essay from an external contributor, who soon thereafter joins the list.

After a delay of almost a week, a multilogue does get off the ground: an

initial round of roughly a week, with several participants and quick

responses, followed by a three-week "panel" discussion in slow but steady

pace between three skilled and knowledgeable contributors, posting long

and reflective messages, which often meticulously respond not to the

latest message, but to the last issue left dangling. A file of the

accumulated text from this multilogue has been circulated on the Xlists on

at least one later occasion where Batesonian questions were in the

mailstream. After a month, one week into March, the facilitator opens the

discussion of the final part of the essay, expressing hopes that the

content of this section will appeal to a wider range of contributors. The

next posting praises this invitation, but also turns out to be the final

posting in the episode - the Bateson reading is alluded to as unfinished

business a month afterwards. Nevertheless, in this episode of joint

reading there is not just a larger number of discussion postings than in

the two previous ones (28 in all), but these postings also form an

interconnected multilogical cascade, which cannot be said about the two

events described previously. The successful character of the Bateson

episode is presumably formed by the concise planning of the event, the

ample time given for preparatory reading (or re-reading) of a classical

and easily available essay, and the presence of a "special guest

contributor".

In the fourth case, the Engeström paper, "Development as breaking away

and opening up" (Engeström, 1996), chosen for joint reading in the autumn

of 1996, the initial phases of the joint reading event develop more

rapidly than in any of the other cases: the episode passes from proposal

to discussion in four days. The paper is selected for joint reading just a

little over a week after being presented at the Second Conference for

Sociocultural Research, held in Geneva, September 11-15, 1996. Some of the

Xlist participants who were not going to Geneva had expressed their

interest in post-conference discussion on the list even before the

conference, and the intention was to take up other papers after the first

one had been treated. Engeström's paper argues against theories of

development that look only to the peaceful and stepwise individual

progress along a universal, pre-established developmental path. It

suggests that individual transformation may depend on collective

transformation, that development may be viewed as partially destructive

rejection of the old - rather than simply as benign achievement of mastery

- and that instead of just being a movement across vertical levels,

development may also involve movement across horizontal borders. The

theoretical arguments of the paper are illustrated by means of examples

from Peter Høeg's novel "The Borderliners" (1994), and its re-formulations

of the Vygotskian Zone of Proximal Development are well in line with Xlist

debates over the years. When the paper is first suggested for joint

reading there is briefly some organisational discussion: other papers are

mentioned, the author posts his agreement, and, following a suggestion

that it would be a good idea to make the target paper available over the

MCA Website, there is discussion about the best procedures for putting

papers on the Web. However, on the third day after the initial suggestion

an electronic copy of the paper is sent over the list, and the next day

there are already responses from contributors who have read it. This event

is different from the earlier occasions of joint reading in being a lot

less pre-planned and in having no designated chairperson. In keeping with

its occurrence in the single-list, high-mailflow era of local history

discussion part of it contains a larger number of contributions than any

of the other three joint reading episodes - 53 postings in the course of

three weeks - and there are many crossreferences between strands of the

cluster, although late in the episode an independent thread on the use of

fiction as data develops, which is related to the paper, but not to the

other strands of the multilogue. When the multilogue is far into its phase

of decay there is an announcement that the paper is now available through

the Web page. One of the two last postings in the episode that arrive

after this point is an attempt to bring together some of the issues

brought up and formulate new questions. There is, however, no uptake to

this. The only difference between this episode of joint reading and a

spontaneously emerging multilogue is the fact that the discussion takes

off from the reading of the Engeström paper and keeps returning to this

text. Evidently the strategy of broadcasting the paper on very short

notice worked well as a way of riding the waves of a self-organizing

system. On the other hand, as with other attempts at initiating a new

multilogue by introducing external material, this strategy is a gamble -

although probably less so when the paper is requested by list participants

than when it is first offered up by the author. (There are many instances

of this in the Xlist archives, and, especially in the early years,

paper-length texts sent over the list were likely to be taken as insults

by at least some subscribers, and responded to accordingly. However, with

increasing Internet access, the floating of bulky material into the shared

setting is less commonly seen as an offense.)

The two cases of successfully carried out joint reading shared the

characteristic lack of closure with spontaneously emerging multilogues.

Trying to rekindle a topic that has started to decay may be no more

feasible than leaving the popcorn in the microwave until every single corn

has popped. However, when the pops get few and far between, the late

contributor might win the day by rhetorically tying up loose ends - it

would seem as if the wily writer could produce a fair simulacrum of

consensus with no great risk of being gainsaid. Perhaps the Xlist custom

of leaving always some questions in the air is to be preferred, even to

the price of the frustration that may arise from the lack of closure.

Concluding remarks: tuning in to mailinglist dynamics The

voluntary nature of participation on a scholarly mailinglist, the

distributed character of both the subscriber pool and the technical

facilities coordinating their communicative activity, and not least the

nature of the activity as a semiotic process all merit the description of

mailinglist activity as a self-regulating system. This paper, in dialogue

with its companion

paper, has explored a number of avenues towards conceptualizing and

analyzing the ways in which the scholarly mailinglist can also be regarded

as a self-organizing system of mathematical complexity, pointing, among

other things, to some aspects which exhibit the inverse power law

relationships that indicate a probabilistic system in a state of

self-organizing criticality. The work of generating a viable conceptual

approach has involved a repeated movement back and forth between the

experience of active participation on a scholarly mailinglist, and the

external perspective mediated by representations of the mailinglist

ecology that serve to maintain distance and provide overviews of parts or

aspects of the mailinglist activity system and its products.

Graphical link maps of intermessage references were introduced as a

tool and used for making the temporal structure of multilogical events and

the relations between messages visible. Three fairly large samples chosen

because of containing interesting multilogical episodes were presented,

and graphically represented by link maps, bridging between the perceptions

of subscribers participating in multilogical activity in its expanding and

dissipating phases and an analytical perspective on the events. The

perception of accelerating intensity in the written conversation that

characterizes the emergence of a multilogical cascade corresponds to an

expansion of the system-internal temporality - when the discussion gets

hot the mailinglist takes more reading and writing time from its active

participants each time they visit the virtual setting - and at the same

time there is an increasing density of interlinkage between postings.

However, the expansion contains the seed of its own dissolution, as with

an increasing number of active messages in the system (relevant postings,

old and new) the collective capacity of participants to hold together the

whole semiotic complexity of the multilogue will reach its limit. The

perception of thematic chaining and dissolution into unrelated branches of

conversation correspond to a spatial drifting apart and loss of

connections in the link map. What has been presented here from this

conceptually generative phase of research naturally demands further

testing of its viability.

However, my observations of the several ways in which the activity on a

scholarly mailinglist can be said to be self-regulating warrant some

concluding remarks in the direction of application. For those of us who

wish to capture the learning potential of written conversation in the

mailinglist medium it is important to be well aware of the self-regulating

nature of scholarly mailinglists, in all senses of the word. If nothing

else it may spare us from some disappointments: a self-organizing system

is not really amenable to control or planned change - but it is,

nevertheless, possible to get in tune with the internal dynamics of a

mailinglist, and learn to recognize the moments when small interventions

have a fair chance of triggering noticeable effects. The four case studies

of more or less planned and successful events of joint reading on the

Xlists illustrate both how plans may go wrong in this distributed and

loosely coordinated medium, and how organized episodes may be carried

through, with the right timing in relation to the current dynamics in the

activity system. The success of a scholarly mailinglist as a multilogical

activity system, then, depends on the apt performance of semiotic

self-regulation in the subscriber community, involving for each and every

responsible participant a coordination of the moments of centered

participation with a certain amount of de-centering towards a view of the

emergent states of the mailinglist ecology. On the Xlists these kinds of

facilitation skills have always been regarded as a collective

responsibility for maintenance of the cultural practices of multilogical

discussion. The combination of the centered, participatory appropriation

of these practices with occasional de-centered knowledge-building about

the emergent nature of mailinglist dynamics at a systemic level would seem

to me a promising road towards maintaining practices of mailinglist

re-centering.

I would like to acknowledge my gratitude

to the whole Xlist community for collegial support, scholarship and

friendship during my years as a virtual neighbor (starting in November

1993). Mike Cole and Arne Raeithel provided me with the encouragement and

inspiration to take up mailinglist dynamics as an object of research. My

quotations of their messages are an expression of my indebtedness: they

"said it all" before I even got there. Any mistakes I have made while

filling in the blanks between their wizardly intuitions and the

cyber-archaeological material are, of course, my own. I would like to acknowledge my gratitude

to the whole Xlist community for collegial support, scholarship and

friendship during my years as a virtual neighbor (starting in November

1993). Mike Cole and Arne Raeithel provided me with the encouragement and

inspiration to take up mailinglist dynamics as an object of research. My

quotations of their messages are an expression of my indebtedness: they

"said it all" before I even got there. Any mistakes I have made while

filling in the blanks between their wizardly intuitions and the

cyber-archaeological material are, of course, my own.

This work was supported by The Swedish Council for Research in the

Humanities and Social Sciences (HSFR).

Opinions are those of the author

and are not necessarily those of the Council.

ReferencesBak, Per. 1996. How Nature Works,

NY:Springer-Verlag.

Barbatsis, Gretchen, Michael Fegan and Kenneth Hansen. 1999. The

Performance of Cyberspace: an Exploration inti Computer Mediated Reality.

Journal of Computer Mediated Communication [On-line], 5 (1).

Available at URL = http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol5/issue1/barbatsis.html

Barowy, William. 1999. A Model for Temporal Self-Regulation in

Electronic Learning Communities. Paper presented in the symposium: Time

and coordination in a virtual community of learners. EARLI (European

Association for Research on Learning and Instruction), Göteborg, Sweden,

August 24-28 1999.

Bateson, Gregory. 1972. Form, Substance, and Difference. In Steps to

an Ecology of Mind. pp. 448-466. New York: Ballantine Books.

Baym, Nancy. 1996. "Agreements and Disagreements in a Computer-Mediated

Discussion", Research on Language and Social Interaction 29(4):

315-345.

Black, Steven. D. James A. Levin, Hugh Mehan and Clark N. Quinn (1983).

Real and non-real time interaction: Unraveling the multiple threads of

discourse. Discourse Processes, 6, 59-75.

Cole, Michael. 1997. From The Creation of Settings to the Sustaining of

Institutions. Mind, Culture, and Activity. 4(3): 183-190

Cole, Michael, and Yrjö Engeström. 1993. A cultural-historical approach

to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (ed) Distributed Cognitions.

Psychological and educational considerations. Cambridge MA: Cambridge

University press.

Decker, William M. 1998. Epistolary Practices. Letter Writing in

America before Telecommunications. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press

Donath, Judith, Karrie Karahalios, and Fernanda Viégas. 1999.

Visualizing Conversation. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication [On-line], 4 (4). Available at URL = http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue4/donath.html

Dooley, Kevin J., and Andrew H. Van de Ven. 1997. A Primer on

Diagnosing Dynamic Organizational Processes. Available at URL: http://www.eas.asu.edu/~kdooley/os.pdf

Ekeblad, Eva. 1998. Contact, Community and Multilogue: Electronic

communication in the practice of scholarship. Paper presented at The

Fourth Congress of the International Society for Cultural Research and

Activity Theory, ISCRAT 1998, Aarhus University, Denmark, June 7-11, 1998.

Available at URL: http://cite.ped.gu.se/Eklanda/Papers/ISCRAT/CoCoMu.html

Engeström, Yrjö. 1996. Development as breaking away and opening up: a

challenge to Vygotsky and Piaget. Paper presented at at the IInd

Conference for Sociocultural Research, Geneva, 11-15 September 1996.

Galegher, Jolene, Lee Sproull, and Sara Kiesler. 1998. Legitimacy,

authority, and community in electronic support groups. Written

Communication 15(4), 493-530.

Gruber, Helmut. 1998. Computer-mediated communication and scholarly

discourse: forms of topic-initiation and thematic development.

Pragmatics: 8(1): 21-45

Herring, Susan. 1999. Interactional coherence in CMC. Journal of

Computer Mediated Communication [On-line], 4 (4). Available at URL =

http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue4/herring.html

Herrmann, Françoise. 1998. Building on-line communities of practice: an

example and implications. Educational Technology, 38 (1), 16-23.

Høeg, Peter. 1994. Borderliners. New York: Farrar, Straus and

Giroux.

Jones, Quentin. 1997. Virtual-Communities, Virtual Settlements &

Cyber-Archaeology: A Theoretical Outline. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication [On-line], 3 (3). Available at URL = http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue3/jones.html

Leont'ev, A. N. 1978. Activity, Consciousness and Personality.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Leont'ev, A. N. 1982. Problems of the Development of the Mind.

Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Lewenstein, Bruce. 1995. Do Public Electronic Bulletin Boards Help

Create Scientific Knowledge? The Cold Fusion Case. Science, Technology,

& Human Values 20(2): 123-149

Levin, James A., Haesun Kim, and Margaret M. Riel. 1990. Analyzing

instructional interactions on electronic message networks. In: L.M.

Harasim (Ed) Online Education. New York: Praeger.

Lotman, Yuri M. 1988. Text within Text. Soviet Psychology, 1988,

Vol. 26, No. 3 pp 32-51

McElhearn, Kirk. 1996. Writing Conversation: An Analysis of Speech

Events in E-mail Mailing Lists. Available at URL: http://www.mcelhearn.com/cmc.html

Moll, Luis. 1997. The Creation of Mediating Settings. Mind, Culture,

and Activity. 4(3): 191-199

Mulkay, Michael J. 1985. The word and the world: explorations in the

form of sociological thought. Winchester: Allen & Unwin.

Palme, Jacob. 1989. Elektronisk post. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Palme, Jacob. 1995. The Optimal Group Size in Computer Mediated

Communication. In J. Palme. Electronic Mail. London UK: Artech

House Publishers. The relevant excerpt is available at URL: http://www.dsv.su.se/~jpalme/e-mail-book/group-size.html

Raeithel, Arne. 1992. Semiotic self-regulation and work. An

activity-theoretical foundation for design. In C.Floyd, H. Züllighoven, R.

Budde & R. Keil-Slawik (Eds.), Software development and reality

construction (pp 391-415). Berlin: Springer

Raeithel, Arne. 1996. On the ethnography of cooperative work. In: Y.

Engeström and D. Middleton (Eds.) Communication and Cognition at

Work. New York: Cambridge University Press

Rafaeli, Sheizaf and Fay Sudweeks. 1996. Networked Interactivity.

Journal of Computer Mediated Communication [On-line], 2 (4).

Available at URL = http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol2/issue4/rafaeli.sudweeks.html

Rojo, Alejandra. 1995. Participation in scholarly electronic forums. A

University of Toronto Ph.D. thesis. Electronically available at URL: http://www.oise.on.ca/~arojo/tabcont.html

Sandbothe, Mike. 1998. Media Temporalities in the Internet: Philosophy

of Time and Media with Derrida and RortyJournal of Computer Mediated

Communication [On-line], 4 (2). Available at URL = http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue2/sandbothe.html

Sarason, Seymour, 1997. Revisiting The Creation of Settings. Mind,

Culture, and Activity 4(3): 170-182.

Shank, Gary. 1993. Abductive multiloguing. The semiotic dynamics of

navigating the Net. Arachnet Electronic Journal on Virtual Culture v1n01

(March 22, 1993) URL = ftp://ftp.lib.ncsu.edu/pub/stacks/aejvc/aejvc-v1n01-shank-abductive

Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer. 1989. Institutional ecology,

'translations' and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in

Berkley's museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-1939. Social Studies of

Science, 19: 387-420.

Syverson, Margaret A. 1994. The wealth of reality: an ecology of

composition. Ph.D Dissertation, UCSD.

Syverson, Margaret A. 1999. The wealth of reality: an ecology of

composition. Southern Illinois Univ Press

Wells, Gordon and Gen-Ling Chang. 1997. "What have you learned?":

Co-constructing the meaning of time. In J. Flood, S. Brice-Heath and D.

Lapp (Eds.) A Handbook for Literacy Educators: Research on Teaching the

Communicative and Visual Arts. New York: Macmillan.

Wells, Gordon. 1993. Reevaluating the IRF sequence: A proposal for the

articulation of theories of activity and discourse for the analysis of

teaching and learning in the classroom. Linguistics and Education

5: 1-37

Vygotsky, Lev.S. 1934/1987. Thinking and speech. In R.W. Rieber and

A.S. Carton (Eds.) The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky, Volume 1:

Problems of general psychology. (Trans. N. Minick). New York: Plenum.

|

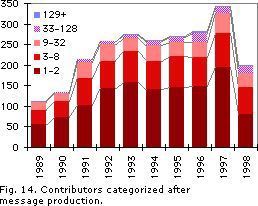

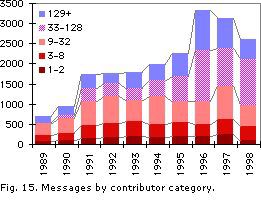

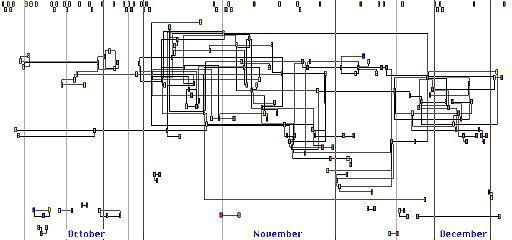

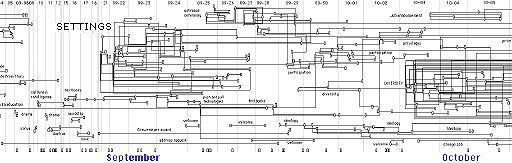

The link maps make visible both differences and

similarities between the three samples. On the side of difference, the

increasing mailflow over the years is evident. An increasing number of

messages are crammed into the same horisontal space, which also represents

a decreasing span of calendar time. There is a corresponding increase in

the density of interactions: the increasing number of links active in

parallel corresponds to an increase in the pool of messages still in

active relationship with writers in the ecology of composition at any

given time. The increasing mailflow is accompanied by an increasing drift

from topic to topic. The Tools Multilogue and the Goals Multilogue both

stand out as the absolutely major event in the channel (or subchannel) for

weeks and months, while the Settings Multilogue competes with several

other topics (see

The link maps make visible both differences and

similarities between the three samples. On the side of difference, the

increasing mailflow over the years is evident. An increasing number of

messages are crammed into the same horisontal space, which also represents

a decreasing span of calendar time. There is a corresponding increase in

the density of interactions: the increasing number of links active in

parallel corresponds to an increase in the pool of messages still in

active relationship with writers in the ecology of composition at any

given time. The increasing mailflow is accompanied by an increasing drift

from topic to topic. The Tools Multilogue and the Goals Multilogue both

stand out as the absolutely major event in the channel (or subchannel) for

weeks and months, while the Settings Multilogue competes with several

other topics (see  In the spatial representation of the link maps a

message cascade necessarily spreads vertically as the number of active

messages in it increases. This serves well as a metaphor for how the

conceptual chains drift apart. As the multilogue unfolds in time it is

simply not possible for each contributor to explicitly take account of all

previous postings in the episode, much less to preserve topical coherence

with them.

In the spatial representation of the link maps a

message cascade necessarily spreads vertically as the number of active

messages in it increases. This serves well as a metaphor for how the

conceptual chains drift apart. As the multilogue unfolds in time it is

simply not possible for each contributor to explicitly take account of all

previous postings in the episode, much less to preserve topical coherence

with them.

The reduction illustrates quite nicely how common

origin may be forgotten as a multilogical episode starts to decay. The

spatial drifting apart of branches corresponds, at least metaphorically,

with the way different strands of a multilogue take up different aspects

of the topic and bring them in very different directions, in the fashion

of Vygotsky's chains and complexes. So the link map shows how the network

of intermessage references gets looser in the decay phase of a cascade.

The frequency of posting goes down, and unless other clusters have started

growing the list-internal timeflow shrinks. While there have certainly

been expiring branches throughout the development of a multilogical

cascade, soon there is no other kind. This is, of course, just a

description in words of what the link map makes visible as the nature of

endings: in the final phase few postings evoke further response, and these

final postings often have little connection with each other. However,

there are also postings even late in the life of an episode that cross

over and tie together nodes widely apart in the net of past messages -

whether by seriously attempted integration, witty application of a phrase

transported from one context to the other, or just a friendly nudge to

neighbours discussing another topic: there are many possibilities. The

exemplar in day 8 of the Settings Multilogue happens to be of the kind

where a latecomer seriously attempts an integration and reformulation of

questions without receiving any further response. This happens with a

certain regularity - individual actions are not enough to turn the tide of

a decaying topic. Visually, in terms of the link map, these postings close

the local structure, but as the genre of summary adopted on the Xlists

seems oriented towards bringing the discussion further, they usually

contribute questions and challenges, which, when left without uptake,

contributes to the unfinished and frustrating quality of multilogical

endings. This may be a point where participants might adapt their

practices to the contingencies of the medium, and learn to produce

"closing turns" to threads that are "running out" - an idea with some

connection to practices of joint reading and other applied forms of

structured events on scholarly mailinglists.

The reduction illustrates quite nicely how common

origin may be forgotten as a multilogical episode starts to decay. The

spatial drifting apart of branches corresponds, at least metaphorically,

with the way different strands of a multilogue take up different aspects

of the topic and bring them in very different directions, in the fashion

of Vygotsky's chains and complexes. So the link map shows how the network

of intermessage references gets looser in the decay phase of a cascade.

The frequency of posting goes down, and unless other clusters have started

growing the list-internal timeflow shrinks. While there have certainly

been expiring branches throughout the development of a multilogical

cascade, soon there is no other kind. This is, of course, just a

description in words of what the link map makes visible as the nature of

endings: in the final phase few postings evoke further response, and these

final postings often have little connection with each other. However,

there are also postings even late in the life of an episode that cross

over and tie together nodes widely apart in the net of past messages -

whether by seriously attempted integration, witty application of a phrase

transported from one context to the other, or just a friendly nudge to

neighbours discussing another topic: there are many possibilities. The

exemplar in day 8 of the Settings Multilogue happens to be of the kind

where a latecomer seriously attempts an integration and reformulation of

questions without receiving any further response. This happens with a

certain regularity - individual actions are not enough to turn the tide of

a decaying topic. Visually, in terms of the link map, these postings close

the local structure, but as the genre of summary adopted on the Xlists

seems oriented towards bringing the discussion further, they usually

contribute questions and challenges, which, when left without uptake,

contributes to the unfinished and frustrating quality of multilogical

endings. This may be a point where participants might adapt their

practices to the contingencies of the medium, and learn to produce

"closing turns" to threads that are "running out" - an idea with some

connection to practices of joint reading and other applied forms of

structured events on scholarly mailinglists.